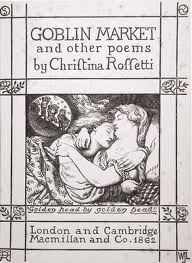

Originally, I wanted to delve into the character of the Femme Fatale-a fierce, seductive, clever woman who turns the rules upside down-but first, I thought it might be helpful to look back at the beginnings of patriarchy, the how and why, through the literature of Jane Austin and Frances Burney.

At some point in Sense and Sensibility, one feels it is something entirely different to Evelina, putting an emphasis on the contradicting economic disparity between the lives of men and women. The details of this contradiction are carefully recorded in Burney’s Evelina as well as Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, in which the social order makes oppressive demands on its members by forcing them to follow a patriarchal code of behavior. This code concatenates an environment where being a woman is of consequence to sexual and emotional vulnerability, allowing masculinity to control by assault as the central expression of power. The gross representation of marriage creates a false air of female autonomy, where women become subjugated by the need of financial support. Conclusively, both novels accept male dominion and marriage as the only form of female subsistence—which without, women would be futile.

“Marriage…for many young middle-class women in mid-eighteenth century England, sustained a double and contradictory ideological value in determining female futurity: although its aspect in much sentimental fiction offered them escape from the ‘gulphs, pits, and precipices’ of maturity,…it rationalized the nonprogressive aspect of female life…which contributes to the good of society…the characteristics of women are isolated as aspects of consciousness which do not threaten male personal or social power”(Straub, 418). Within this double standard of morality, Straub is suggesting that two spheres exist: public and private. The public sphere is masculinity, while the private encases women in their domestic duties of being good wives, mothers, and guardians of morality—that is, submitting to the patriarchal code. Wondered among readers though is why women allow themselves to exist through men. “Aware that dependency on the family was a burden…and given almost no options for self support which would not sink them below the rank of gentlewoman, women were constrained to marry” (Newton, 48). Both Evelina and Sense and Sensibility uncover the precarious situations of single women in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the marriages of convenience as the only possibility of financial and social security.

In both novels, men, no matter how hapless or undeserving, are provided for and given every opportunity to earn their way. Conversely, women were prepared for nothing but display— not to accomplish, but be accomplished. “Burney visualized women as dependant—economically, physically and psychologically—on men” (Brown, 394). Therefore, all a respectable young women could do to alleviate the strain and uneasy status of being unprovided for was to marry. However, “men were marrying late, and when they did marry, men were likely to require a dowry. Add to this the legal subordination of wife to husband and it is clear that the fate of the middle class woman was bound to a relationship that was at once necessary, risky, and difficult to achieve” (Newton, 48). Burney’s ideology is that marriage is a women’s only destiny, requiring patience and cautiousness in displaying oneself and waiting to be chosen. And so, The History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World, is really the tale of Evelina’s debut into the “marriage market” (Newton). The various operas, balls, plays, and garden events Evelina attends not only accustom her to mainstream society, but function as circumstances in which she can display herself for men. Becoming Londonized, Evelina describes the sensation of her new appearance: “how oddly my head feels, full of powder and black pins, and a great cushion on top of it” (Burney, 22). The same London that allows Evelina to feel affection for herself is also a city by which women are preyed upon. Becoming an object, liability, and more importantly, marketed merchandise, Evelina is facilitated to undergo a series of trials where she falls quarry to men who villainously attack her virtue. The same quality of economic dependency that drives a women seek a husband, also allows easy assumption that they may be pursued and attacked. At Evelina’s “first assembly she is provoked by Lovel’s ‘negligent impertinence,’ at her second, ‘tormented’ to death by Sir Clement. A trip to the opera marks her first kidnapping, and an evening at the play, a public attack. At the Pantheon a licentious Lord affronts her by staring, and at Vauxhall strange men ‘rudely’ seize upon and pursue her until she is almost ‘distracted with terror” (Newton, 50). Evelina had hardly go anywhere in public without being violated. London, in all its immoral glory, permits the abuse of women. Mr. Smith, the picturesque gentleman of the Branghton and Duvall’s company, characterizes the economic contradiction between men and women, and the resulting inequality in terms of status and power. He is aware that women are economically dependent on men and tells Evelina that “marriage is all in all with the ladies; but with us gentlemen it’s quite another thing!” (Burney, 209). Also aware of his position as a buyer in the market, he is pleased that “the law of supply and demand makes him the treasure” (Newton, 48): “there are a great many other ladies that have been proposed to me…so you may very well be proud…for I assure you, there is nobody so likely to catch me at last as yourself” (Burney, 211). The male privileges in the market allow Smith to feel it is rightful of him to impose his will upon women. He becomes astounded when Evelina refuses his invitation to the assembly, and becomes manipulative: “advancing to take Evelina’s hand” (Burney, 221), and forcing Madam Duvall to command Evelina’s attendance. “Lord, Ma’am, come, come don’t be cross…your Grand-mama shall ask you, and then I know you’ll not be so cruel” (Burney, 182). After unsuccessfully sporting Evelina’s attendance at the assembly, despite Madame Duvall’s reprimands, Smith decides to use his strength in obliging Evelina to his personal contentment. “As we were walking about the orchestra…Mr. Smith, flying up to me, caught my hand and, with a motion too quick to be resisted, ran away with me many yards…though I struggled as well as I could to get from him, insisting upon stopping (Burney, 228). Aside from Smith, young Branghton, Evelina’s cousin, has also an ill affectation to gallantry. He readily assumes that those who provide economic relief have the right to dictate. He insists on paying for Evelina’s coach fares and tickets, believing that “if I pay, I think I’ve a right to have it my own way” (Burney, 174). Like Smith, Branghton is also wary that women are dependent upon men and marriage for subsistence. The consciousness of money and its relation to male superiority, status, and control, it is vulgarly portrayed in Smith and Branghton as a fallible habit.

At her first ridotto, Evelina encounters someone even more dangerous than Mr. Smith and Branghton—Sir Clement Willoughby: a steadfast pursuer of Evelina’s virtue. When his forward courting approach does not reciprocate tender feelings, Willoughby attempts to take advantage of Evelina’s inexperience by using his superiority and manipulative manners to create situations in which she cannot avoid without being polite. An early example of such subversion takes place at Evelina’s attendance to her first public, social event. When confronted by Willoughby who asks her to dance, Evelina refuses his partnership by lying that she has already been invited to dance by someone else. Willoughby persists to badger her about the mystery man who she has invented to evade his presence. Imposing presence over protest, Willoughby forces Evelina to dance, insisting that “it cannot be that you are so cruel! Softness itself is painted in your eyes— you could not, surely, have the barbarity so wantonly to trifle with my misery!” (Burney, 51). Reluctantly, Evelina finally succumbs to his wishes, tolerating his manipulation of her response. In a separate escapade, Willougby kidnaps Evelina after a ball, so deeply terrifying her that she contemplates leaping from the chariot door. Whilst she calls out the window for help, Willoughby assures her that “my life is at your devotion” (Burney, 97). And to ease her strife, Sir Clement “poured forth abundant protestations of honour, and assurance of respect for having offended [Evelina], and beseeching [her] good opinion”(Burney, 88). Good opinion indeed: Burney goes so far as to let Evelina prefer Sir Clement over Mr. Smith. “It is true, no man can possibly pay me greater compliments, or make more fine speeches, than Sir Clement Willoughby: yet his language, though too flowery, is always that of a gentleman; and his address and manners are so very superior,…that to make any comparison between him and Mr. Smith would be extremely unjust” (Burney, 163). A positive response to Sir Clements’s forward courting, Evelina suggests then, that the dominion of men over women is not arbitrary, and is in fact acceptable. In other words, without men as assailants of marriage (no matter how forward or harsh they be), women would have no other reason to exist.

The related concepts of dependence, independence and choice unite Sense and Sensibility with the later novel in terms of status. To be labeled as independent, one must be governed by their own will. Conversely, to be dependent means to be governed by the will of others. In Austen’s texts she deems reliant characters as incomplete human beings. In contrast, those who maintain their independence are thought to be the greatest and most powerful class in society by terms of hierarchy. Therefore, social events and behavior are regulated by a patriarchal order, where values are based on the possession of property, and the females are subordinated to males in family and society.

Similar to Evelina, the characters within Austen’s text concern themselves with the mutable fortunes of their social classmates. As the most important social contract, marriage is a primary concern. The widow of Henry Dashwood and his three daughters are economically disadvantaged by the transfer of property between generations through a male heir. Dependent, thus incomplete, the Dashwood sisters look upon their brother John for relief. The unfavorable circumstances of women encouraged beautification and attractiveness as proper means to secure a husband: “It would be an excellent match, for he was rich and she was handsome” (Austen, 38). This projects female vulnerability by emphasizing the sexual dangers that confronted young women, namely seduction, where she is prized overall for her physical attraction. In this, Austen adapts a new counter revolutionary fear—that through reliance on their own judgment and emotions, young women would succumb to temptation from the wrong suitor. Marianne is the prime example of this, for she falls for the dangerous and false charm of Willoughby. Willoughby appears to be gentleman of romantic, honest, and genuine gesture. However, he reveals himself to be vain, idle and cruel— appearance deceiving in actuality. The plot of Sense and Sensibility is largely driven by the deception of its characters. Edward misleads Elinor concerning his marital availability, and the intentions he has toward her. Willoughby deceives Marianne about his character, and his past, current, and future entanglements. “We have seen that, as it affects Marianne, the plot is the popular myth of subversion: new, individualistic ideas (sensibility) encouraged by a specious rootless stranger, Willoughby, bring her not to seduction— the subverted heroine’s usual fate—but to the verge of death” (Butler, 103). Marianne’s ailment, the climax of her story, is seen as a consequence of challenging and defying the partriarchal code. Her sensibility shaped her into too much of an individualistic person for society and her own good, where she cannot depend on her own judgments and emotions. And so, after being guided by her intuition since the beginning of the novel, Marianne’s sickness leads her to realize her position in society as demanded by men with fixed rules and respect. Marianne’s sensibility kindled her rude, unfair and unkind behavior to her mother, sister Elinor, Mrs. Jennings, Mrs. Ferrars, and Edward Ferrars himself. “Sensibility, one of the typically human-centered concerns of the expansive era, is now in the reactionary period identified as egotistical, solipsistic, and potentially anarchic,” (Butler, 104) all of which if featured by women, pose a threat to patriarchy. In the end, the unions Marianne and Elinor achieve prove to be of profit for them, but only after immense suffering and social disgrace. “The power of male deception…is presented by Austen as an outcome of a particular social organization…of the vitiating tendencies of patriarchy” (Perkins, 109). Perkins suggests that perhaps the mobility of men allows them to be deceivers. Throughout the novel, men have a mobility that women do not. It is more in their personal lives that men are seen to have more autonomy than women, to come and go as they please. “It may be a patriarchal formality of the society within the novel that men of the middle and upper ranks are almost unlimited in their freedom of movement about the nation, whereas women of similar rank are sharply constrained in their mobility. Willoughby and Edward have only to get on their horses to be able to move” (Perkins, 116). The patterns of movement suggest a dramatic difference between the sovereignty of men and women. Young genteel women could have been as mobile for men if they were not in an oppressive social state. Mobility provides a duality for which men could fractionate their lives between unrelated places, using deception to excuse them from unwanted confrontation, and ultimately reward them with more than one woman; therefore suggesting that women are replaceable if found undesirable or futile.

The outcomes of Evelina and Sense and Sensibility reward a woman’s apprenticeship with marriage, and more importantly, financial and social security. However, the means by which women became wives relied heavily on dressage and beauty, which as its consequence, subjected women to sexual and emotional violence. The patriarchal code of society not only denied each heroine autonomy, but by fairytale ending, suggests male dominion over women is acceptable and in fact necessary. Mobility, wealth, and the knowledge of being desirous are all that prompted men in the pursuance, rather abuse of women. Such females who resisted the conventional hierarchy, like Marianne Dashwood, were made to have an epiphany of the rightful position of females in society. Allowing these thoughts to conquer, both novels are in acceptance of female oppression. For without the purposeful title of wife: women “who contribute to the good of society… isolated as aspects of consciousness which do not threaten male personal or social power” (Straub, 418) women would be futile, becoming but a burden upon their families.

References

Austen, Jane. Sense and Sensibility. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002.

Burney, Frances. Evelina. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997.

Butler, Marilyn. Romantics, Rebels, and Reactionaries: English Literature and its Background

1760-1830. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Newton, Judith. “Evelina: Or, the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the Marriage

Market.” Modern Language Studies spring 1976: 48-56. Vol.6, No. 1.

<http://www.Jstor.com>.

Perkins, Moreland. Reshaping the Sexes in Sense and Sensibility. Charlottesville: The University

Press of Virginia, 1998.

Straub, Kristina. “Evelina: Marriage as the Dangerous Die.” Evelina. Ed. Stewart J.

Cooke. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997. 411-430.

Tags: Burney, domestic sphere, dowry, England, Evelina, Frances Burney, hierarchy, Jane Austen, London, Marriage, patriarchy, sense and sensibility