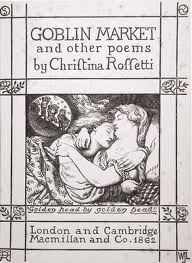

Christina Rossetti’s “Goblin Market” is the type of poem I cherish not only because it’s lucid, lively, and genius for its time, but because there are so many ways of interpreting the language.

It’s freezing here in Jersey, it’s hump day, I got out of work early… my first thought…”I have plenty of time to lose myself.” This is what I came up with. Some ideas are not exactly complete, but I’m sure it will rain or snow in the next few weeks-giving me plenty of time to revise 😉

****

Goblin Market, under the veil of sisterhood, narrates the homosexual relationship between sisters, Laura and Lizzie. The text speaks on the nature of homoeroticism amongst women, and its influence upon the dominant patriarchal code. This code accommodates an environment where being a woman is of consequence to sexual and emotional vulnerability, allowing masculinity to control by assault as the central expression of power.

Karl Marx in Capital, (Das Kapital) defines a commodity as “an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of sort or another” (Marx, 125). Marx attempts to explain that a commodity is only valued in relation to demand or otherworldly conditions, and therefore is an ideal item for the capitalist economic system. The relationship between the materiality of an item and its perceived societal value is illusory—It’s value solely determined by desire.

In her book, This Sex Which is Not One, Luce Irigaray uses Karl Marx’s definition of commodity relations and values within the capitalist market, in comparison to the cultural structure and values of patriarchy’s own ‘market,’ which she asserts pre-dates capitalism: “From the very origin of private property and the patriarchal family, social exploitation occurred…all the social regimes of History are based upon the exploitation of one class of producers, namely women” (Irigaray, 173). Irigaray substitutes men as the ‘exploiters,’ a position Marx reserves for capitalists. She argues that under patriarchy women are oppressed, serving only as exchangeable property, while men are “exempt from being used and circulated” (Irigaray, 172). Irigaray’s interprets female homosexuality from the response of patriarchy, as a product which is to be consumed—a commodity—in which women become men because the code of patriarchy dictates that only a man can desire a woman. Irigaray questions, “what if these ‘commodities’ refused to go to market? What if they maintained ‘another’ kind of commerce, among themselves?” (Irigaray, 196). Irigaray believes female refusal to participate in masculine society would allow for a new society to form, in which, women are empowered and masculine systems of barter abandoned. Goblin Market also seeks for utopia, as throughout, the sisters challenge the conventions of patriarchy. However the end is troubling, whereby it ends not with abolishment of the patriarchal code, but a restoration of it through childbirth.

Goblin Market can be interpreted as both a didactic story of the importance of sisterhood, and a subversion of patriarchy, whereas Rossetti creates a world devoid of masculine hostility, where women are dependent on one another. Laura and Lizzie live in a feminine society which is depicted as ideal. However, each evening the utopia is threatened by goblin men who are selling their seductive fruits. They become a catalyst in the sisters’ transition from childhood into adulthood, and allow them to also realize their sexual potential, thus destroying their utopian, female society.

Whereas Laura is wary of the goblin men by warning her sister of their intentions, she is not strong enough to resist their temptation. Lured by the chanting, “come buy, come buy” (Rossetti, 4) and the exoticism of the produce that “men sell not such in any town,” (Rossetti, 101) Laura submits to exchanging a lock of her golden hair for the fruit. Irigaray observes that “heterosexuality is nothing but the assignment of economic roles: there are producer subjects and agents of exchange on the one hand, productive earth and commodities on the other” (Irigaray, 192). By substituting her hair for money, Laura ‘commodifies’ her body—allowing the men to determine the terms of the purchase, and situate herself within the patriarchal economy whilst rejecting participation in the female community. Through force, Lizzie is able to rescue her sister from the economic code of the goblin men, and create a new society which closely resembles Irigaray’s vision of utopia for women, where they possess agency and “exchanges occur without identifiable terms, without accounts, without end” (Irigaray, 197). However, before this new society can be formed, both sisters must negotiate within the goblin men’s economy.

When Lizzie goes to the goblin market she assumes the masculine role of “an agent of exchange,” (Irigaray 192) when she carries her coin. The goblins though, reject her money and therefore deny recognizing her as an equal agent of exchange. They try to force her to eat their fruits, rubbing them into her skin, and saturating her with their juices in a violent manner which echoes sexual and physical abuse. Lizzie manages to be triumphant against the goblin men, and while holding her coin, rejoices to Laura,

“Come and kiss me.

Never mind my bruises,

Hug me, kiss me, suck my juices

Squeezed from goblin fruits for you,

Goblin pulp and goblin dew.

Eat me, drunk me, love me;

Laura make much of me” (Rossetti, 465-72).

Laura offers Lizzie her body, requesting nothing in exchange. What follows is an erotically charged, homosexual salvation, as Laura is saved by consuming the juices from her sister’s skin. It can be said that sexual love offers a fulfilling experience of healing, much like spiritual devotion. As the sisters are brought back together, their utopia can be more fully realized. “Nature’s resources would be expended without depletion, exchanged without labor, freely given, exempt from masculine transactions: enjoyment without a fee, well-being without pain, pleasure without possession” (Irigaray 197). Laura and Lizzie have placed themselves outside the control of the masculine system; however they have not abolished it. They may be able to save themselves as well as each other, but their children will have to fight for themselves.

The poems ends with a restoration of the patriarchal system as the sisters grow old and become wives and mothers, albeit men are absent in the text. Their children, who are sexless, are told to honor sisterhood, “for there is no friend like a sister” (Rossetti, 562). While the concept of sisterhood is supportive and comforting, it is a continuity of patriarchy. Although women can save each other, they cannot change the system that endangers them. Laura and Lizzie can therefore only hope that the ideals of sisterhood and warnings of the goblin men will prevent their children from falling victim to patriarchy.

The ending of the poem seems to be detached from the earlier sequences. The diction of the poem changes as well as the goblin fruits that were initially described as “sweeter than honey from the rock/ stronger than man-rejoicing wine/ clearer than water flowed that juice” (129-31). They now become “like honey to the throat/but poison in the blood” (554-55). The illusory pleasure and sensual nature of the fruits has been realized. This transition from fantasy into reality also brings a restoration of order. Rossetti appears to imagine a world in which sisterhood triumphs over patriarchy, however the ending in which Lizzie and Laura submit to the order by marriage and procreation, subverts Rossetti’s utopia into sheer intangibility of sole hopefulness. Sisterhood can triumph over patriarchy, but only temporarily—it cannot sustain it.

Sisterhood functions in Goblin Market as a way for women to save one another from the code of patriarchy. Women can disable masculine oppression, but only temporarily. While Laura and Lizzie are able to be victorious over the goblin men, their feat has no causality of change for their condition. Instead of fostering the new society which Irigaray envisions, the sisters reincorporate themselves into patriarchal society, thus allowing the system to persist